Seilerstaette

the future looms, curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff

Anna Andreeva, Jordan/Martin Hell, Charlotte Johannesson, Lorenza Longhi, VNS Matrix, Melika Ngombe Kolongo

Curated by, Vienna. The gallery festival with international curators in Vienna.

September 10 – October 22, 2022

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

Charlotte Johannesson

Rocket, 1981 - 1986

Original plotter print

23.5 × 31.5 cm / 42 × 52 × 3.50 cm (framed)

Courtesy the artist, Layr, Vienna and Hollybush Gardens, London.

Charlotte Johannesson

White Flag, 1981 - 1986

Original plotter print

23.50 × 31.50 cm /42 × 52 × 3.50 cm (framed)

Courtesy the artist, Layr, Vienna and Hollybush Gardens, London.

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

Lorenza Longhi

Untitled: Anonymous and timeless, 2022

Leather, brooch, spy camera, glass, paint, plastic; LCD screen, Tv box, wood, resopal, plexiglass, glue, magnets, video

Variable dimensions

Lorenza Longhi

Untitled: Anonymous and timeless, 2022

Leather, brooch, spy camera, glass, paint, plastic; LCD screen, Tv box, wood, resopal, plexiglass, glue, magnets, video

Variable dimensions

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

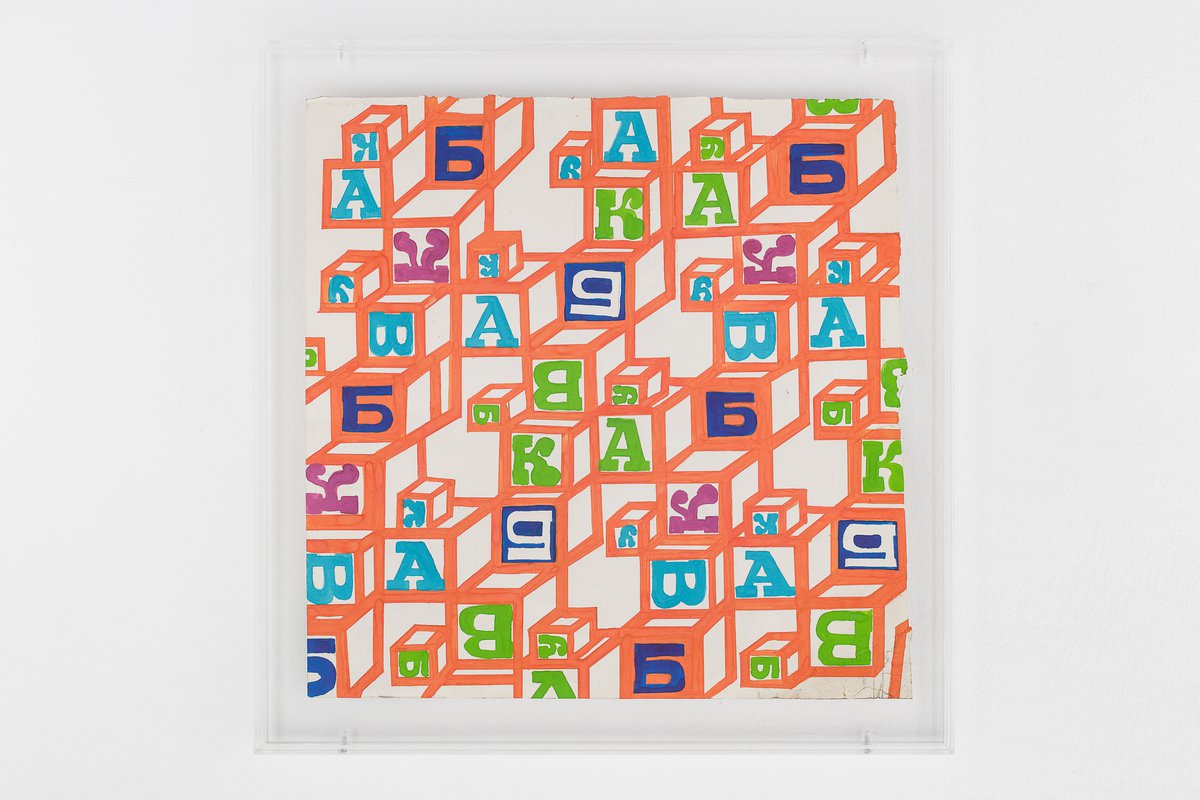

Anna Andreeva

Preliminary Sketch, 1967

Gouache and pencil on paper

36 × 38 cm (framed)

Anna Andreeva

Little Cubes (Sports), 1969

Ink, gouache and pencil on paper

52 × 62 cm (framed)

Anna Andreeva

Little Cubes (Numbers), 1978

Ink, gouache and pencil on paper

49 × 49.5 cm (framed)

Anna Andreeva

Little Cubes (Alphabet), 1965

Ink, gouache and pencil on paper

50 × 51 cm (framed)

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

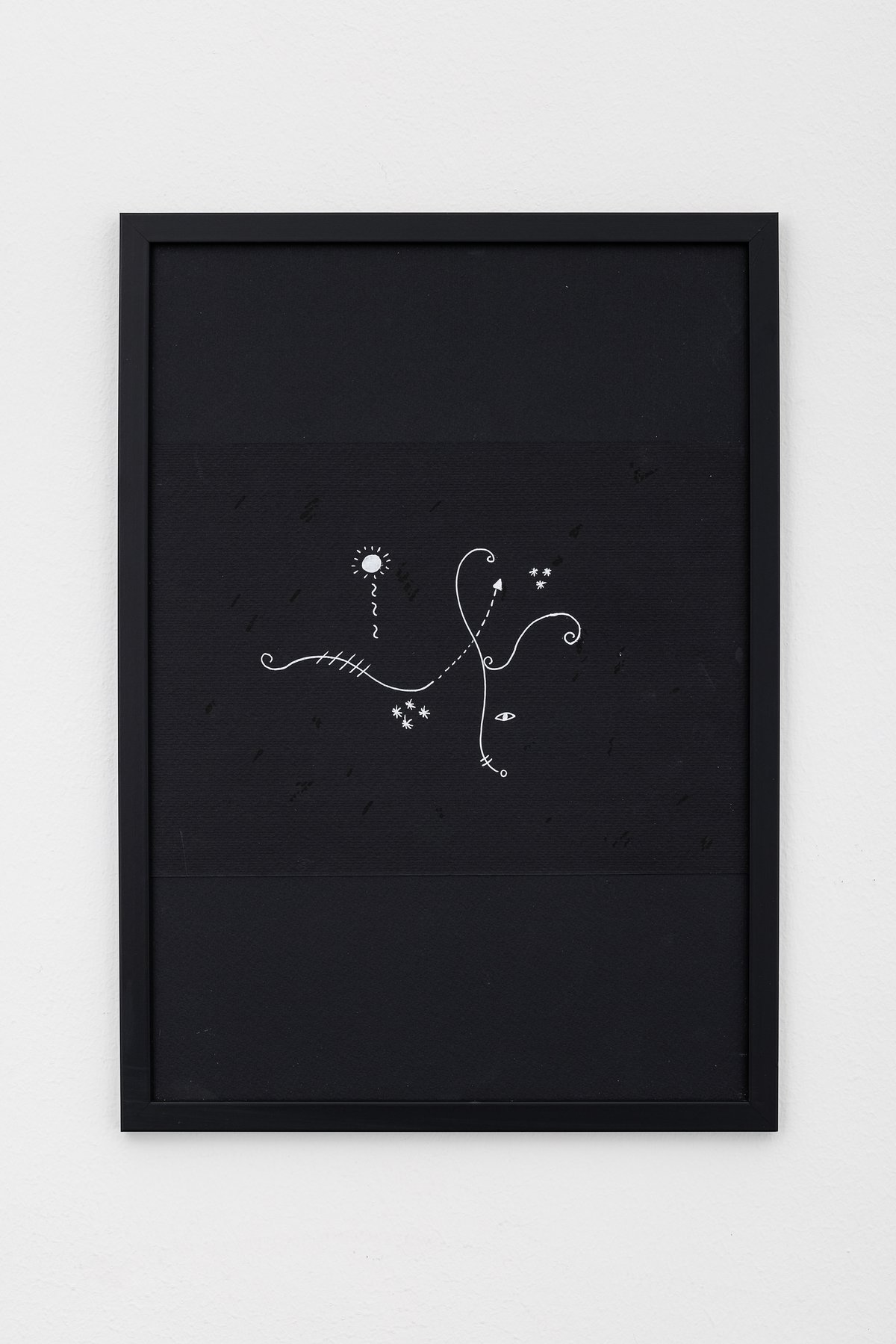

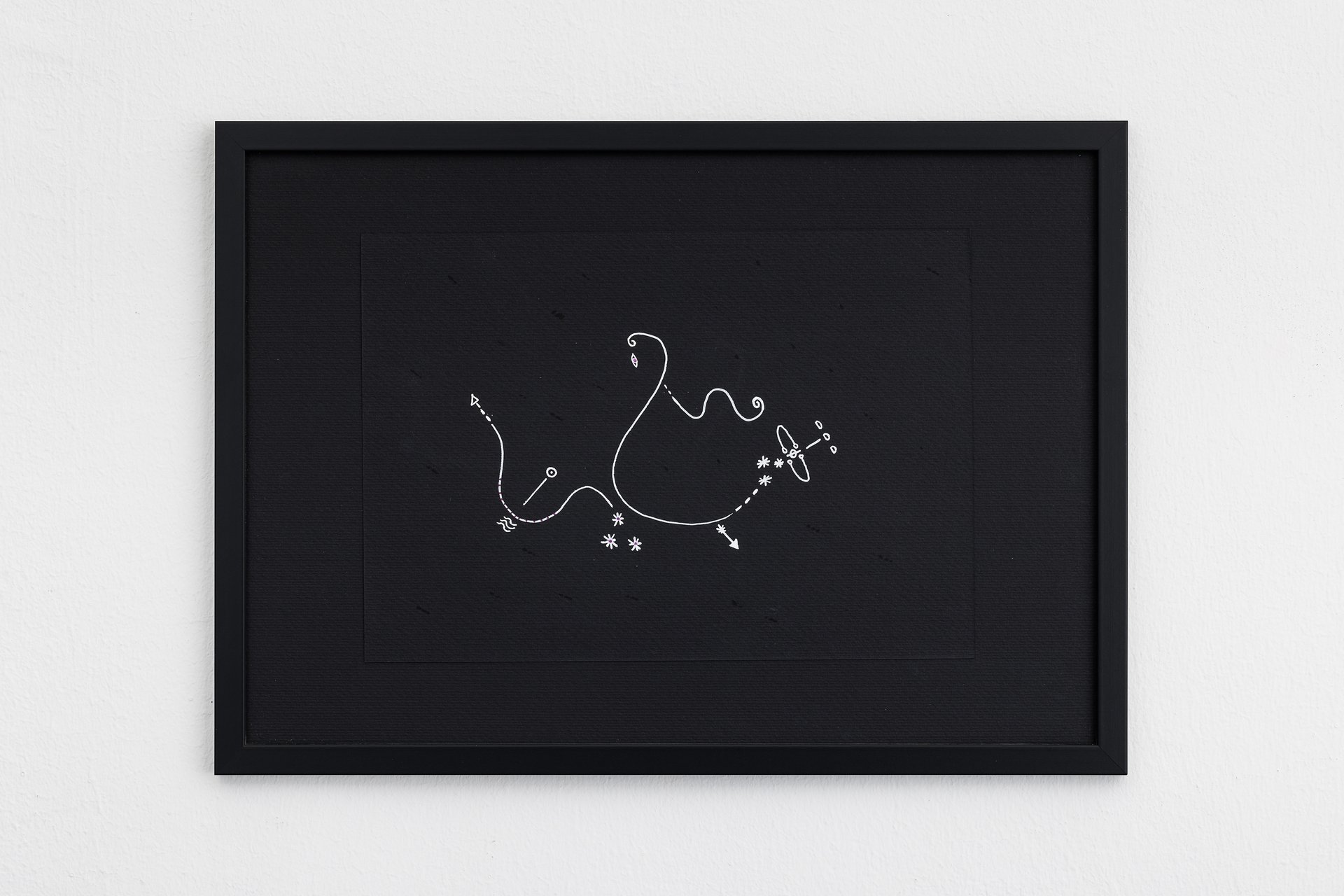

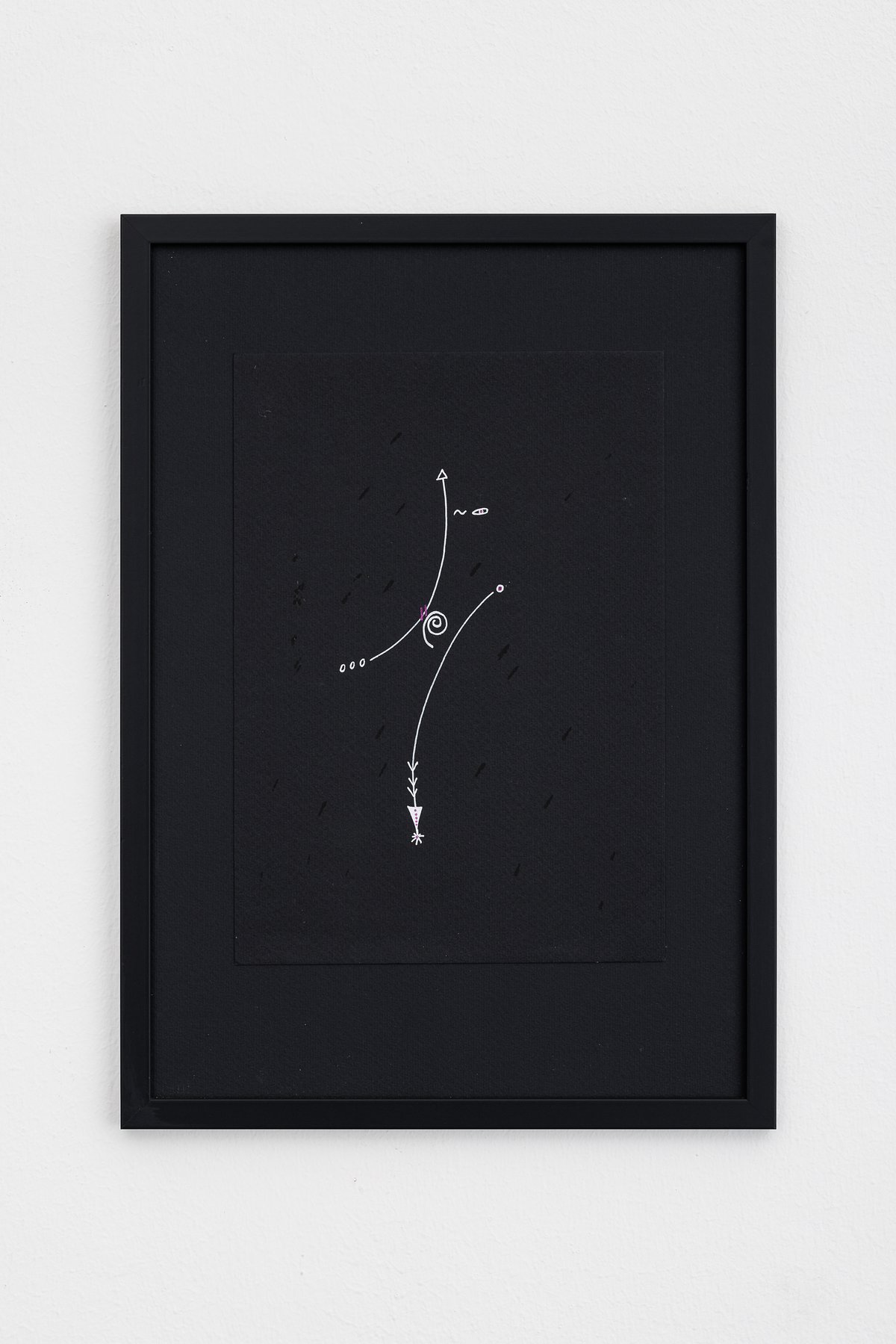

Melika Ngombe Kolongo, Crossroads #01, 2022, Acrylic pen on paper, 42 × 29,7 cm (framed)

Melika Ngombe Kolongo, Crossroads #02, 2022, Acrylic pen on paper, 42 × 29,7 cm (framed)

Melika Ngombe Kolongo, Crossroads #03, 2022, Acrylic pen on paper, 42 × 29,7 cm (framed)

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

Melika Ngombe Kolongo, #9, 2022, Cement, spray paint, found objects, 17 × 17 × 7 cm

the future looms curated by Elisa R. Linn & Lennart Wolff, 2022

Installation view

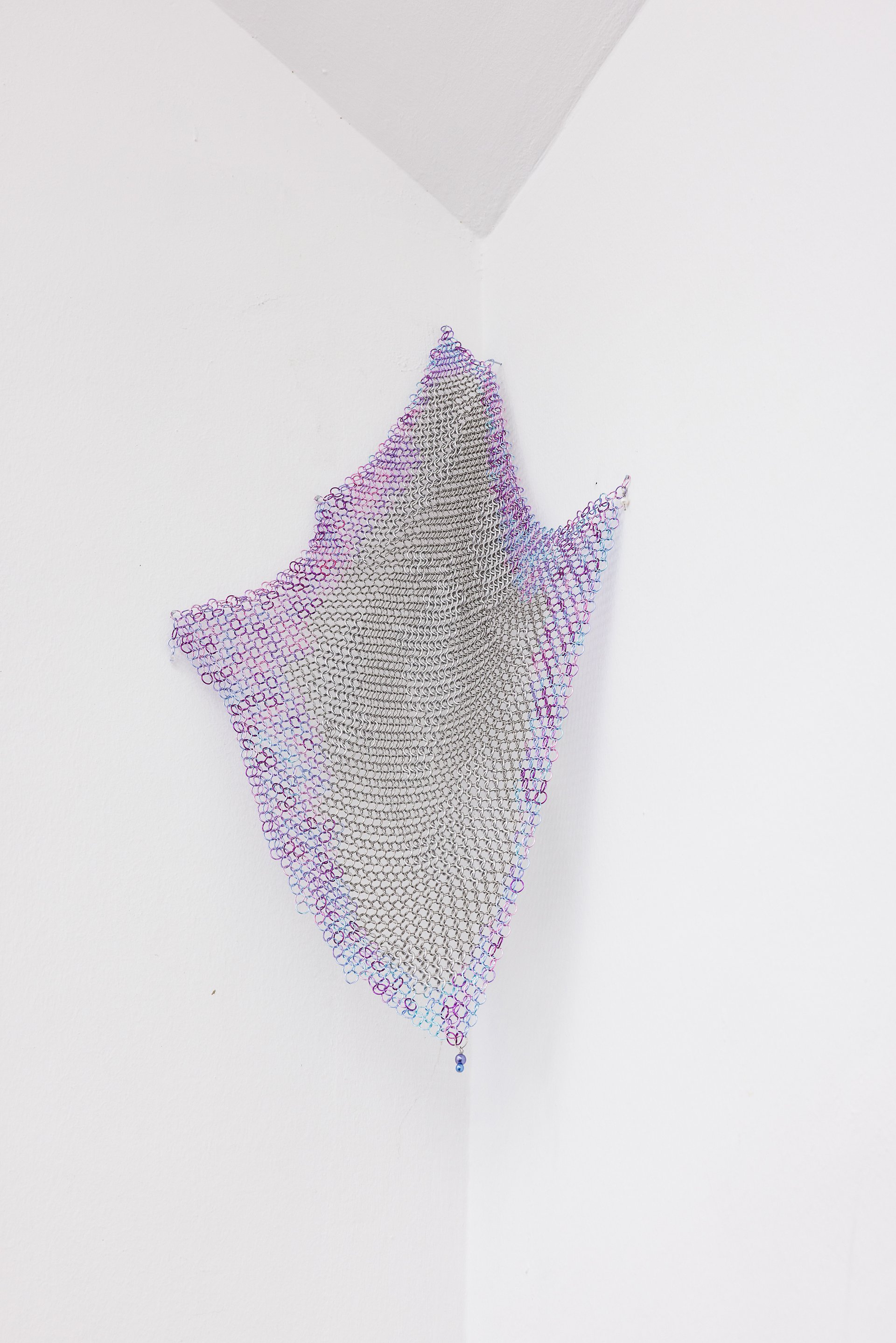

Jordan/Martin Hell

Babooshka (for Anna Andreeva), 2022

Pink & silver chainmail with beads & charms

30 × 30 cm

Jordan/Martin Hell

I'm From The Government, 2022

Acrylic, laser cut on plexi, wood, plastic, ribbons, horse hair, & hair beads

42 × 52 cm

Jordan/Martin Hell

INTERCOURSE, 2022

Car and bike tires, metal carabiners & chains, zip ties

30 × 20 × 10 cm

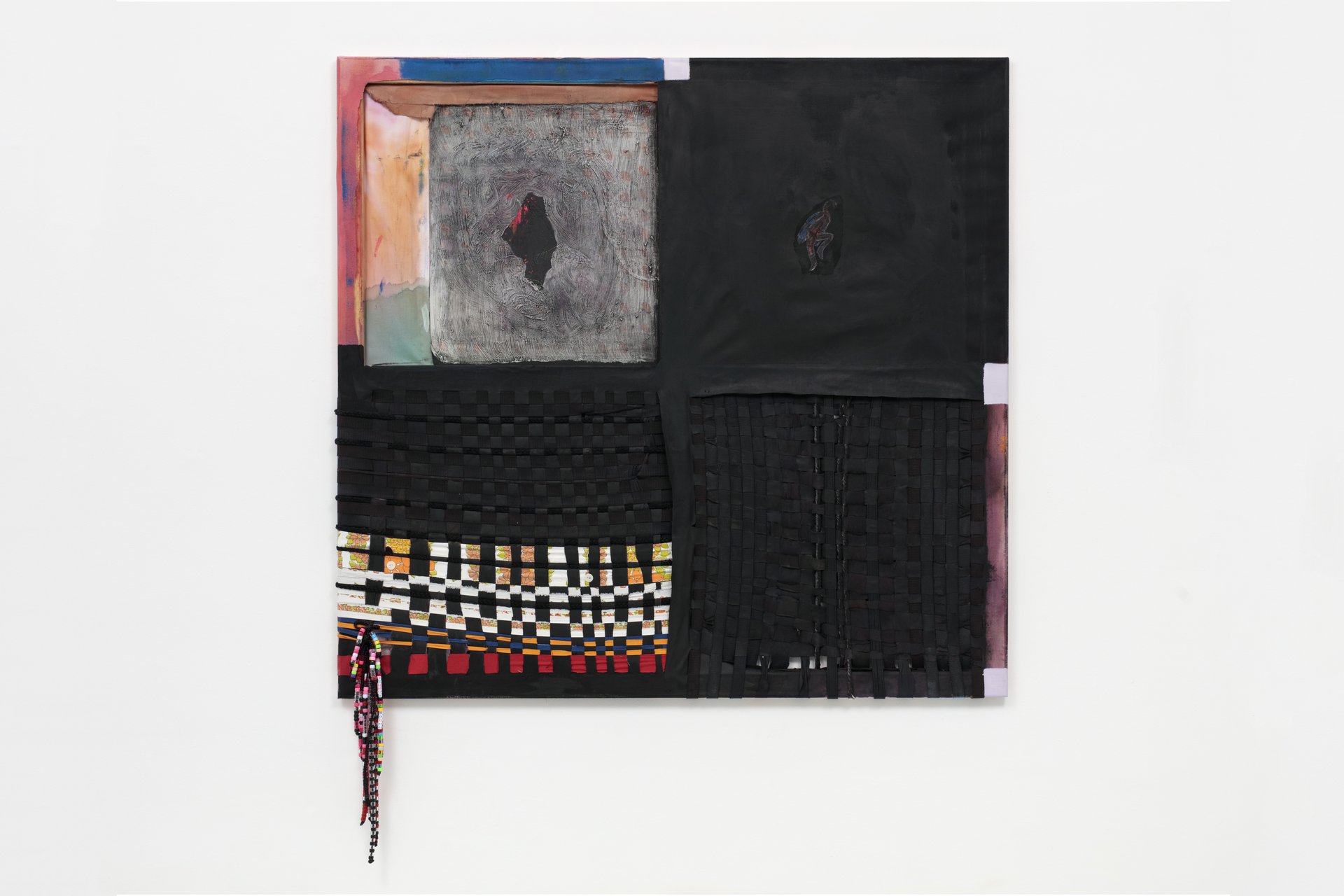

Jordan/Martin Hell

Church on a Hill, 2021

Fabric, acrylic, dye, synthetic hair, hair beads

138 × 115 cm

Anna Andreeva

1/2 of the Moon, 1961

Ink and gouache on special gosznak paper

52 × 52 cm

Different threads are woven together to create a “whole cloth,” which is greater than the sum of its parts: a fabric. For its physicality and tangibility, fabric is also commonly employed as a metaphor for what is complex and abstract: a system or an order—the fabric of society, a nation, or even the cosmos. In information technology, fabric is used synonymously with a framework or platform. Hence, weaving—or rather, “ordering”—connects and assigns roles and positions to each of the interrelated strands, based on rules, boundaries, binaries, and containment that implicate inclusion and exclusion. The modern computer emerged from weaving, the quintessential “women’s work,” according to Sadie Plant; early looms used binary code based on algebra. Ada Lovelace, the “first programmer,” made the loom the vanguard of proto-software development. With Charles Babbage and his Analytical Engine, they laid the foundation for algorithms and computer technology that came to transform not only production and consumption but also warfare. In the 1950s, when IBM started mass-producing its 701 computer, the escalating competition between East and West, NATO, and the Warsaw Pact mobilized computing machines and thinking such as cybernetics—the study of circular causality and feedback—as they were perceived as opportunities to catapult one’s bloc to the forefront of modernity. In the Soviet Union, formerly banned and persecuted scientific fields such as cybernetics returned with the death of Stalin, the “Father of Nations,” as the propagandists named him, and inspired artists and designers to experiment with mathematical formulae. Anna Andreeva, a prominent and much-lauded designer, occupied an ambiguous position as a non-party member and partner of scientist Boris Andreev, Gulag prisoner and later developer of the first Soviet computer. Heading the Krasnaia Roza [Red Rose] silk factory in Moscow, named in honor of Rosa Luxemburg, Andreeva “programmed” patterns for machine-produced fabrics. Worn by prominent figures such as Raisa Gorbacheva and the masses alike, they were the fabrics of society. These hand-drawn geometric and mathematically constructed patterns could only exist in the realm of applied arts, a medium in which avant-garde ideas “survived.” Only thus could they evade being purged as “pure propaganda of abstraction.” Complicating a binary between Socialist Realism and Abstraction, these patterns employed aesthetics officially decried as “Western” and “bourgeois” to communicate socialist visions. Hence, to defend her Electrification Series (ca. 1960s–1974) in front of the committee, Andreeva appropriated Lenin’s developmental slogan: “Communism is synonymous with industrialization and electrification of the whole country.” While cosmism as a utopia and philosophical movement only continued to exist on the margins of collective imagination, it was the technological successes of space travel that led the state in the 1960s to request patterns on the subject from Andreeva. In turn, she had to frequently argue that her designs were not about cosmologies such as moons, stars, and meteoroids—heterodox subjects associated with superstition, irrationalism, and mysticism. Here fabrics for children, seemingly trivial and hence less regulated by ideological restrictions, allowed Andreeva to further develop cybernetic thinking and algorithmic design into analog compositional systems. Basic geometric shapes—little cubes [kubiki]—inspired by El Lissitzky’s Story of Two Squares (1922) amounted to a “program” that could “process” different motifs, signs, and letters. In non-aligned Sweden in the late 1970s, Charlotte Johannesson, a trained weaver and self-taught artist, traded her textile artwork I’m No Angel for an Apple II Plus computer. Johannesson, active in the punk and countercultural scenes, was deeply influenced by the work of Swedish-Norwegian artist Hannah Ryggen, who enhanced weaving with wool, linen, and holes as an unruly medium for social satire, private myths, and folk art. In the 1980s, alongside her involvement in the independent art and research platform Digital Theater (Digitalteatern), which she co-founded with her partner Sture, she produced an array of printed images. These “woven digital graphics,” as she calls them, were coded to the exact same pixel dimensions of her analog loom and depicted artists and politicians like Boy George or Ronald Reagan, world maps, and abstracted and satirized political imagery in what might be read as speculation on a fully networked, cybernetic future. One in which binaries such as gender identities, the domestic and public, private and political, and analog and digital are razed. In 1991, after the fall of the Berlin wall, the Cyberfeminist Manifesto, written by a group of artists named VNS Matrix, demanded a new art for the twenty-first century. As the “terminators of the moral codes, saboteurs of big daddy mainframe,” they claimed the clitoris as a direct line to the matrix. To corrupt the discourse of the new status quo world (dis)order, they imagined tools for conviviality in cyberspace: chatrooms, message boards, billboards, or an interactive computer game for a dynamic space conceived by holes in the so-called social fabric. Against modernist fallacies and their colonial dimensions, artist and musician Melika Ngombe Kolongo uses Geomancy (“magic of earth”) as a prehistoric re-patterning of living matter, as a speculative practice, paranormal storytelling device—a system of divination. In a geomantic network, it is believed that ley lines, as topographic constructs and hidden patterns embedded in a landscape, carry high-vibrational energetic information around the planet, a sort of quantum technology of crossroads “between worlds.” In ancient Congolese cosmologies, geomantic technologies are akin to the secret principles of minerals. Today, a global extractivist machinery commands unidirectional material flows from South to North.. Here, “‘Modern’ technology extracts and captures these electro gravitational waves; they open portals through their intense electromagnetic fields and magnetic behavior as high-frequency, high-power electronic connectors.” Lorenza Longhi appropriates and subverts via re-making and re-printing consumer objects such as furniture and fabrics from the design detritus of late modernism. A Camelia flower handmade by the artist using fabric mimics the perfect symmetry, the “classic and consistent ordering of the petals” that has become a timeless and continually reinvented form for the fashion house Chanel. With its pistil replaced by a micro camera and communicating with a screen, here conspicuous consumption takes place under “surveillance capitalism,” triggering a psychosocial type of surveillance based on the need for self-reflection and portrayal. A novella by Jordan Martin/Hell consists of vignettes and speculative dialogues from polycentric and non-essentialist perspectives on power, hierarchies, hate, and love. The subconsciouses of fictional personas mutate and alter into their actual opponents, sometimes until their effacement. The threads of stories are visually reflected in sculptures and wall works that propose parapsychological landscapes that challenge any differentiation between the concrete and the abstract. Here, varied pieces of fabric, bows made from ribbon, strings of pearls and pigtail braids support or spell out names, hallucinatory figures, or quotes such as Reaganism’s “nine most terrifying words”: “I’m from the government & I’m here to help.” In the future looms, the non-division of hand and head, the ongoing mutation of organic and artificial, past and future, technological and cyborgian, form “the thinking- feeling-doing-matter of the cosmos.”